Warning: I am jumping in late, here, but have taken time to watch attentively and pinpoint a few things which may be of interest to watchers of the drama. Starting this as episode 20-21 are airing, there will be more to be added, so please be patient as this is still "under construction"

Warning: I am jumping in late, here, but have taken time to watch attentively and pinpoint a few things which may be of interest to watchers of the drama. Starting this as episode 20-21 are airing, there will be more to be added, so please be patient as this is still "under construction"

The long linked posts are tied together through the "table of contents" below ("sections" are linked directly through titles there, although some scrolling down may be needed if MDL software does not link exactly to chapter start).

TABLE OF CONTENTS Direct links to sections:

(*) scroll down from target reached if target point remains imprecise for that "chapter" Sources : MDL, Sohu, Baidu, Weibo, Douban, Wikipedia and other articles, recordings from YouTube, Youku, Weibo or other media. (highlighted texts lead to sources ; most pictures lead to their source or further information, except simple screenshots from the drama). Gifs are my own except stated otherwise. To view the list of my other drama companion pieces (with links to them), check : HERE. This companion piece is still under construction ;) |

4. Character relationship charts and Alphabetical list |

Under construction

| A |

| B |

| C |

| D |

| E |

| F |

| G |

| H |

| I |

| J |

| K |

| L |

| M |

| N |

| O |

| P |

| Q |

| R |

| S |

| T |

| U |

| V |

| W |

| X |

| Y |

| Z |

Link back to Table of Contents

5. Characters and cast by order of Appearance(part1 - episodes 1-5) |

Under construction

Pictures : actor/actresses Weibo, MDL and other, links to their sources if not screenshots from the drama

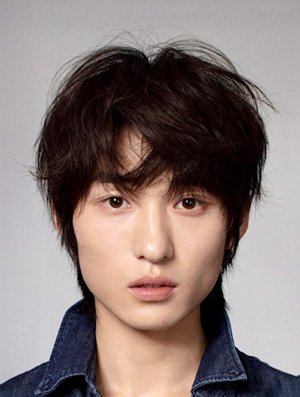

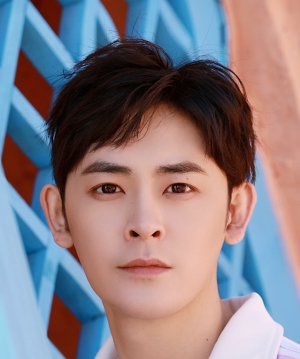

| 1. Jì Guī Nán 季归南 The craftsman had created the Shǔ hóng 蜀紅 red silk dye and won a competition with it. |

| ||

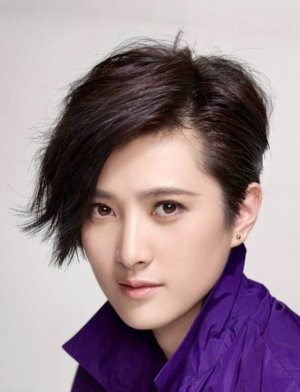

| 2. Shǎo Jì Yīngyīng 少季英英 Daughter of the Master dyer Jì. She was traumatized by the brutal death of her father, and had trouble remembering later what secret her father had told her, and who saved her, having further developed a phobia of blood and red color. |

Obs: she is not Amanda Liu, namesake b.August 22, 1998 who did not play nor sing in Thirteen Years of Dust. | ||

| 3. Liú Jǐnguān 刘锦官 He had checked the silk tribute together with Jì Guī Nán, but still accused him of having substituted fake silk |

| ||

| 4. Dūyùn guān supervisor 督运官 He slit the throat of Jì Guī Nán to silence him. Reappearing in ep.19, he was forced to confess, but was silenced too. | |||

| 5. Shǎo Yáng Jìnglán 少杨静澜 Young Yáng Jìnglán often rode horses and gave a lift to young Jì Yīngyīng to check what was happening at her home. He warned her to be silent "like a rabbit". |

| ||

| 6. Shǎo Jì Yàotíng 少季耀庭 He was Jì Yīngyīng's elder brother, who trained as weaver and stayed close to their mother. |

| ||

| 7. Jì Xú shì 季徐氏 Madame Jì Xú, mother of Yàotíng and Yīngyīng only wanted to stay out of trouble. She threatened to take her life in public when creditors went too hard on her family after they were pardoned but left destitute. She managed to stave them away while her children grew up. Later, she was afraid of her daughter wanting to dye Shǔ hong silk and only wanted to send her far away to marry someone who would not drag her into danger. |

| ||

| 8. Jì Guì 季贵 The family butler could not help with much. |

| ||

| 9. Shǎo Zhào Xiūyuán 少赵修缘 His father stopped him from running to Yīngyīng when her family was taken away in shame, but he managed to convince his dad to help the Jì settle back into an empty house, once they were pardoned. |

|

Ten years later, washing silk threads at 浣花溪 Huàn huā xī (Huàn huā creek)

Ten years later, washing silk threads at 浣花溪 Huàn huā xī (Huàn huā creek)

A versatile actress with a flexible face, she can play adolescents as well as businesswomen or a commercial flight pilot! She also sings quite well. She owns a border collie called Liao Liao.

Nicknames : Xiǎo Tán 小谭 , Xiǎo Sōngshǔ 小 松鼠 ("little squirrel"), Jingjing, Liang Xiaojie ; Fandom Name: Sōngguǒ 松果 (Pine Cone) ; Fandom Color: Sky Blue ; Fanchant: sōng yùn chī hǎo shuì hǎo, sōng guǒ péi nǐ dào lǎo(松韵吃好睡好,松果陪你到老) 25.156 million fans on Weibo, as of December 2024.

| 10. Jì Yīngyīng 季英英 The fearless and stubborn girl wanted to make things right. She will be developing two colors: her own pink red and her father's Shǔ red, proud to have them registered in Chang'an, and displayed on the wall of colors of Yizhou Brocade Bureau. |

She mostly played in modern times dramas, such as the girl in 2020 Go Ahead, but also in a memorable ancient costume role alongside an "embroidered officer" played by Rèn Jiālún in 2019 Under the Power, and as an embroiderer in 2021 The Sword and the Brocade, set in Ming dynasty. | ||

| 11. Chén sānláng 陈三郎 Third Mr. Chén, from the minor 映溪染坊 Yìngxī Rǎnfáng (Shining brook Dyehouse) was an optimist who loved to sing, and one of the faithful friends of Yīngyīng. among the first to join the "Silk Society" |

| ||

| 12. Shèng dàláng 盛大郎 Mr. Shèng, from minor 彩鸾染坊 Cǎiluán Rǎnfáng (Splendid fabulous bird Dyehouse), liked to sing, and always carried a medicine box because his mother thought he was frail! |

He appeared in 8+ dramas and a movie in support roles since 2020 | ||

| 13. Zhū xiǎoniáng 朱小娘 Miss Zhū, nickname “Pín” 玭 (Pearl) was the daughter of the owners of 落霞染坊 Luòxiá Rǎnfáng “sunset clouds dyehouse”). She was Yīngyīng's best friend and also did not want to marry just to please her parents. |

| ||

| 14. Jiǎng Liùláng 蒋六郎 Sixth Mr. Jiǎng, from 流月染坊 Liúyuè Rǎnfáng (Flowing moon dyehouse), was on the lookout for his friends and also a faithful friend of Yīngyīng , joining the Silk Society from start. |

Since 2014, he appeared in 16+ dramas and 7 movies. He has also worked as screenwriter for 2019 short (30 mins) comedy movie Knight of Time | ||

| 15. Huā Xiǎngróng 花想容 The Huā family’s son-in-law (Huā Róng’s henpecked husband), he helped her hinder the lesser dyers at the creek, to cause them to enter debts. |

He appeared in 35+ dramas and 4 movies since 2018. | ||

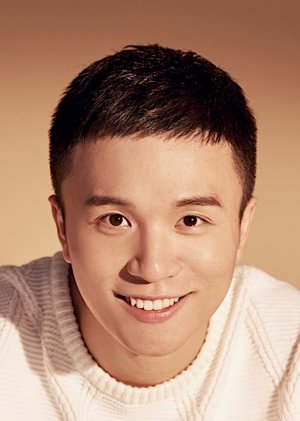

| 16. Sāng shísì (Sāng 14) 桑十四 Chief Sāng’s son who liked gambling, accepted to be honorary president of the Silk Society, and fell in unrequited love with Miss Zhu. |

|

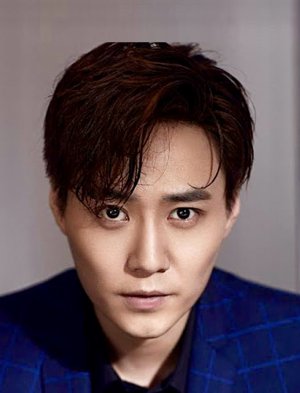

Following a dispute with his former agency he did not renew with them after contract expired in 2021, and operates now under his own agency, Zheng Ye Cheng Studio.

Nickname: Dà Chéng 大成 ; Fandom Name: Xiǎo yèzǐ 小叶子 ("Little Leaf") ; Fandom Color: Green ; Fanchant: dà chéng, dà chéng, méi nǐ bú chéng (大成,大成,没你不成)10.8 million fans on Weibo , as of December 2024.

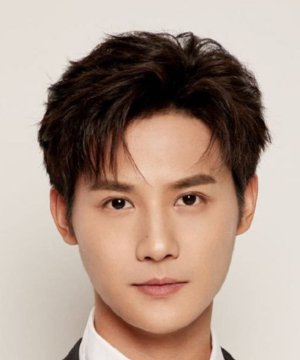

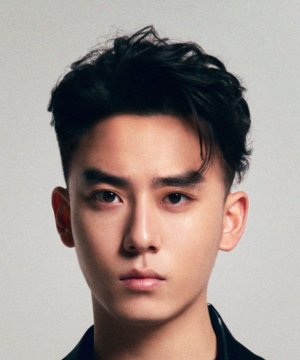

| 17. Yáng Jìnglán 杨静澜 He was the new “brocade officer” arrived unannounced and stayed relatively low key for a few days, while starting his inquiries. His mission was: reproduce the Shǔ 蜀 red silk, investigate the murders of his predecessors, and reform the brocade industry in Yìzhōu 益州. |

| ||

| 18. Jì Yàotíng 季耀庭 Yīngyīng’s weaver brother, fascinated by "innkeeper" and martial artist Yù Línglóng |

| ||

| 19. Guo Kui The dog of Jì family scared people like Huā Róng but was friendly from start with Yáng Jìnglán. | |||

| 20. Huā Róng 花容 Owner of Huā ’s Dyehouse, wife of Huā Xiǎngróng (who was at her beck and call), she was ruthlessly pushing smaller businesses to bankruptcy to buy them out as a front for a more powerful player, who was specially targeting Yīngyīng and the Jì family. Thus, she seized Yàotíng's loom to lure him into a trap. |

| ||

| 21. Zhū Gé Hóng 诸葛鸿 He had come as a subordinate of Yáng Jìnglán but was more a friend and trusted help in the investigations |

| ||

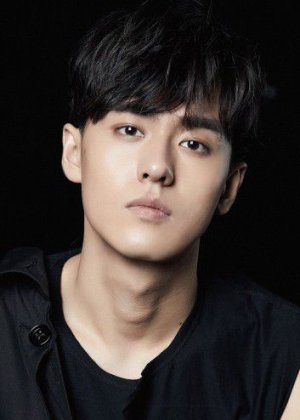

| 22. Zhào Xiūyuán 赵修缘 He was Yīngyīng’s betrothed from childhood, although his father did not agree after the downfall of the J family. Yīngyīng believed he was the one who understood her the most. They often signaled via a kite and met on a bridge. But faced with a tough choice, he believed the best way to save her was to appear like he yielded to her enemies. This was going to wound Yīngyīng more than he imagined and he could never force her back to him later, when he "grew in power". |

Zhang Hao Wei, who had to take a pause in his career mid 2024 because of a lawsuit to fight against possibly malicious accusations. The AI "facelift" helped production not having to put the drama on the shelf for indefinite time because of one actor's problems. | ||

| 23. Dishonest patron of the inn The anonymous man tried to take advantage of the 月不还 Yuèbùhuàn innkeeper or slander the establishment but was kicked out while Yīngyīng watched. | |||

| 24. Yù Línglóng 玉玲珑 Ms Yù, martial artist and innkeeper of Yuèbùhuàn 月不还 (‘gives no credit’) ; she still helped Yīngyīng with a loan to help her win a gamble which might profit her inn. She was Yáng Jìnglán’s former sister-in-law (ex wife of Yáng Jìngshān) and recognized him immediately, but did not tell others. |

| ||

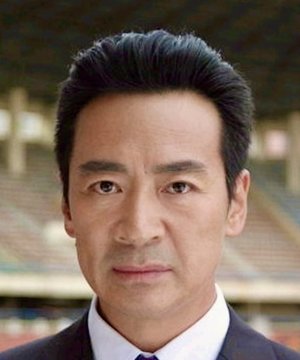

| 25. Sāng Shèn 桑慎 aka Chief Sāng (桑长史 Sāng zhǎng shǐ) The (interim) “brocade officer” Chief of the Brocade Bureau was astounded that his son Sāng shísì (Sāng 14) was in the game to promote business and the sale of silk embroidered 荷包 hébāo (propitious pouches) and a member of the new Silk Society. |

| ||

| 26. Zhào Shēn shì 赵申氏 Madame Zhào, "Shēn niáng", was Zhào Xiūyuán's mother. She was opposed to the marriage of her son to Yīngyīng and acted coldly around the Jì family. |

| ||

| 27. Brocade Bureau servant Yang Jìnglán’s new subordinate of the Brocade Bureau first brought a message from de Yáng residence, and later shadowed suspects for the investigation. | |||

| 28. Niú wǔniáng 牛五娘 The mysterious face scarred lady was the real mastermind behind the Huā clan. She was the daughter of general Niú (vice commander, see ep.8), a ruthless scheming person who used anyone for her profit and power games. |

| ||

| 29. Yú Shū 于殊 The silk house owner, who had bought the former Jì workshop, being saddled with debts, could not help Yīngyīng enter the brocade competition. |

| ||

| 30. Yú Xī 于溪 Yú Shū’s granddaughter played with a silk ball (see section about the Xiùqiú ) |

| ||

| 31. Zhào lǎotàiyé 赵老太爷 (Grandpa Zhào) Master of Zhào silk house, patriarch of the family, he set conditions to help Yīngyīng join the Splendor Showcase with the Silk Society. |

| ||

| 32. Yáng Jùxián 杨聚贤 Yáng Jìnglán loathed his father, after the death of his mother whom his dad had been all but abandoned for Shēn niang. |

| ||

| 33. Yáng Shí shì 杨石氏 Madame Yáng was the Yáng family matriarch. |

| ||

| 34. Yáng Jìngshān 杨静山 Eldest son of Yáng the family and Master weaver, he was also the former fiance of Yù Línglóng who had broken with her. |

| ||

| 35. Yáng Jìnglín 杨静林 Second son of Yáng the family |

| ||

| 36. Wáng Zhǎngguì 王掌柜 "Shopkeeper Wáng" praised Yàotíng who had come to work for him after Mrs Huā seized his loom, but it was only to have him beaten by jealous colleagues. Yàotíng signed a contract to redeem the broken loom of his father which Wáng had purchased, but the dishonest shopkeeper in collude with Mrs Huā accused him of stealing it and refused to show the contract. |

| ||

| 37. Sarcastic shopkeeper He added fuel to fire to discredit Yīngyīng who had been forced to act out of character by Mrs Huā (who threatened her with breaking her brother’s legs and wrists for theft !) at the Léi Zǔ festival | |||

| 38. Overseer The overseer of the secret workshop on Qīngchén mountain worked for Niú wǔniáng. | |||

| 39. Yù Yuán 玉缘 Faithful maid of Niú wǔniáng (who was willing to take punishments for her boss) ; she informed her that Yáng Jìnglán had bought his title as silk commissioner to spite his family. |

| ||

| 40. Zhào Píng 赵平 The Zhào family attendant, despite being close to Zhào , could not deliver a letter to the J family, as the Zhào patriarch had forbidden contact with them after the scandal at the festival. |

|

Link back to Table of Contents

6. Characters and cast by order of appearance(part 2 - episodes 6-14) |

Under construction

| 41. Sūn Zhǎngguì 孙掌柜 Wáng Dyehouse won 3rd prize ; Sūn got 2nd prize ; Mrs Huā Róng was first : all had their bribes return as "prize"! |

| ||

| 42. Brocade bureau officer Subordinate of Yáng Jìnglán who investigated Ms Huā and the mountain (ep 7 and 10) | |||

| Ep.8 | 43. Niú fūrén 牛夫人 Madame Niú, mother of girls including , was living mentally diminished in the Niú mansion after a difficult delivery many years before. Niú wǔniáng tried to convince Yīngyīng to join her side by telling her the sob stories of her life, but Yīngyīng refused. |

| ||

| 44. Servant of Niú wǔniáng who was instructed to force Yīngyīng to make Shǔ red dye and held her prisoner in a hidden cellar while Yang searched the grounds. |

| 45. Niú Jǐn 牛瑾 The general was vice commander of Jiàn nán 劍南 region, under the military commissioner M. |

| ||

| 46. Zhāng Cìshǐ 张 刺史 Governor Zhāng welcomed general Niú riding back into the city ; he was the military commissioner’s eye in Yizhou. |

| ||

| 47. Gāo Fàng 高放 |

| ||

| 48. Yóuxiá yǐ 游侠乙 Ranger B |

| |||

| 49. Yóuxiá jiǎ 游侠甲 Woman Ranger A |

| |||

| 50. Bái Shéng 白晟 / Bái zhǎngguì 白掌柜 Merchant Bái from Nánzhào 南詔 wanted to enter the silk brocade community, and was interested in an ancient sacred design. His interest in Yīngyīng grew and he helped her finally create the silk brocade tribute. |

| ||

| 51. Bái fǔ púcóng 白府仆从 The Servant of the Bái had come from Nánzhào with his master. |

| ||

| 52. Judge Judge at the Brocade Weaving competition. | |||

| 53. ZXiude Zhào Xiūyuán’s brother suspected that Zhào Xiūyuán and Niú wǔniáng would bring trouble to the family. Little did he expect to what extent : Zhào Xiūyuán demanded that the patriarch (see 31) step down and hand the position. | |||

| 54. Níng Dài 宁黛 Bái Shéng’s junior had covertly gathered information about the brocade families in Yizhou, naming three to be worth of attention : Yáng, Zhào, and Yú. She mentioned Jì Yīngyīng knew how to dye the Shǔ red silk but ‘did not know how to weave’. |

| ||

| 55. Zhū fù 朱父 He was angry about the disobedience streaks of his daughter. |

| ||

| 56. Zhū mǔ 朱母 Pín's mother also wanted to set up blind dates for her daughter. |

| ||

| 57. Niángzǐ jiǎ 娘子甲 'Lady A' was | |||

| 58. Shěn Rúfēng 沈如风 Yáng Jìnglán had flashbacks of memory about him |

| ||

| 59. Liú Lǎobó 刘老伯 Old uncle Liú was the Gubei village chief, guardian of the God of grain brocade. |

| ||

| 60. Liú èr 刘二 He needed money to take care of his sick mother. |

| ||

| 61. Cūnmín jiǎ 村民甲 Villager A |

| |||

| 62. Cūnmín 2yǐ 村民2乙 Villager 2B |

| |||

| 63. Mù Huī 穆辉 He was the Military commissioner of Yizhou |

| ||

| 64. Xuē Yù 薛煜 He assisted Yáng Jinlan in his investigations about the silk escort, chosen from the military camp. |

| ||

| 65. Zhīgōng jiǎ 织工甲 Weaver A |

| ||

| 66. Dù Yǔ qīzǐ 杜宇妻子 Dù Yǔ’s wife |

| |||

| 67. Dù yǔ nǚ'ér 杜宇女儿 Dù Yǔ’s daughter |

| |||

| 68. | ||||

| 69. | ||||

| 70. | ||||

| 71. | ||||

| 72. | ||||

| 73. |

Link back to Table of Contents

7. Characters and cast by order of appearance(part 3 - episodes 15-20 ) |

ep.15 | 1. | |||

| 2. | ||||

Link back to Table of Contents

8. Characters and cast by order of appearance(part 4 - episodes 21-40 ) |

ep.21 | 1. | |||

| 2. | ||||

Link back to Table of Contents

9. Places of interest in the drama |

Under construction

- Shǔ and Yìzhōu countries or provinces

- Yì zhōu city, Huàn huā xī and Sān dào yàn

- Jiànnán

- Qīngchéng mountain

- Nánzhào

1. Shǔ and Yìzhōu countries or provinces

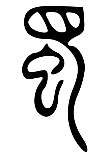

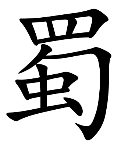

Shǔ in seal script |   | Shǔ in regular script |

(more)

2. Yì zhōu 益州

Yì zhōu 益州, Yì Province or Yì Prefecture, was a zhōu (province) of ancient China. Its capital city was Chéngdū 成都.

During the Hàn dynasty, it included the commanderies Hànzhōng 汉中, Bā 巴, Guǎnghàn 广汉, Shǔ 蜀, Wénshān 文山, Jiànweī 建威, Zāngkē 牂牁, Yuèxī 越西, Yìzhōu and Yōngchéng 雍城. It was bordered in the north by Liáng Province 涼州 and Yōng Province 雍州. At its greatest extent, Yì covered present-day central and eastern Sìchuān 四川, Chóngqìng重庆, southern Shaanxi/Shǎnxī 陕西 and parts of Yúnnán云南 and Guìzhōu 贵州.

| The Yìzhōu in the drama and book refer in fact to the name of Chéngdū 成都 during Táng dynasty , not the Yízhōu 宜州 in north Guǎngxī 广西 Zhuàng autonomous region with its karst mountains along the river Lóng Jiāng 龙江 (Dragon river : famous for its natural scenery and scenes from the 2006 film, The Painted Veil, were filmed along its course. ) But since the filming took place in Guǎngxī there are glimpses in the drama of a karstic appearance artist's imagination of a "Sān dào yàn" (screenshot below) : |

|

浣花溪 Huàn huā xī (Huàn huā creek) still exists in Chéngdū, and Sān dào yàn 三道堰 too, but the landscape is rather flat, since the city is on a plain.

Huàn huā xī in the drama (screenshot) Huàn huā xī in the drama (screenshot) |

3. Jiànnán 劍南

Statue of Liú Bèi Statue of Liú Bèi |  Jiànmén guān and the plank road Jiànmén guān and the plank road |  Tourists on the narrow plank road in 2020 Tourists on the narrow plank road in 2020 |

In the first reign year of Táng dynasty 唐王朝 emperor Tàizōng 太宗 (627 AD), previous administrative divisions were abolished and Yìzhōu 益州 was renamed Jiànnán dào 剑南道, under the Chéngdū fǔ 成都府 (prefecture), because of its location south of the Jiànmén guān 剑门关 pass ("Sword Gate"). The dangerous pass is mentioned in a poem by Dù Fǔ 杜甫 (712-770), at the time of the Táng dynasty collapse. It was a major military place where many battles were fought.

Jiànmén pass today still features the ancient plank road, and there are statues celebrating for instance Liú Bèi 刘备 crossing the pass, Kǒngmíng 孔明 aka Zhūgě Liàng 诸葛亮 digging out the pass.

4. Qīngchéng mountain

View of Qingcheng mountains from the 老君阁 Lǎojūn gé (Lǎojūn pavilion) View of Qingcheng mountains from the 老君阁 Lǎojūn gé (Lǎojūn pavilion) |  Chāoyáng cave entrance Chāoyáng cave entrance |

Close to Chéngdū in Dūjiāngyàn 都江堰, the Qīngchéng mountain (青城山 Qīngchéng Shān ) is home to Dūjiāngyàn Giant Panda Center and since 2000 has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. There are 36 peaks and 11 Taoist temples on mount Qīngchéng. The 36 summitsare in a yin yang type laid out in a circle, with steep cliffs. They are « green in the fours directions » and look like a city wall, hence its 青 Qīng (=green) 城 chéng (=city) name.

Located at the foot of Mount Zhàngrén 丈人山 (old name of the Qīngchéng mountain), the first Taoist temple was Jiànfú Palace (建福宫 Jiànfú gōng) built in the Táng dynasty. Leading figures of the Taoist school are worshiped in the splendid Main Hall."

Located at the foot of the main peak of Mount Laoxiao, the ChāoyángCave (朝阳洞 Chāoyáng dòng) is deep, with drops of water falling down occasionally. Chāoyáng Cave is also a Taoist temple built under steep cliffs which are part of the terrain. The Cave faces the east with the rising sun im the morning and "the front arch at the entrance hangs in the air, making the temple a secluded and refined place."

Qīngchéng Shān 青城山 was affected by the Wènchuān 汶川 Earthquake in 2008.

5. Nánzhào 南詔

Click on the picture above to watch the video about Nánzhào posted to YouTube (9 mins 44)

Click on the picture above to watch the video about Nánzhào posted to YouTube (9 mins 44)

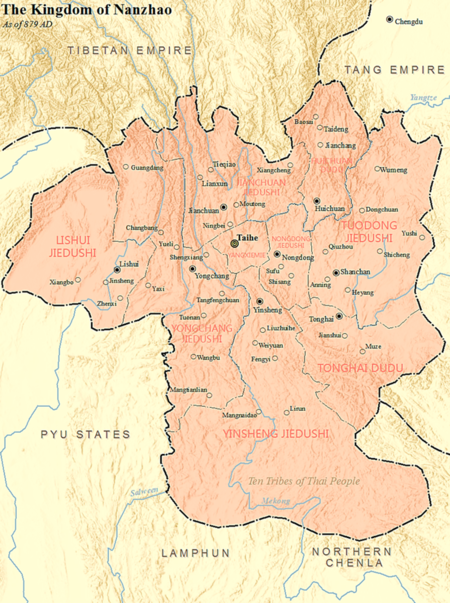

Nánzhào, meaning 'Southern zhào', was a dynastic kingdom that flourished in what is now southwestern China, during the mid/late Táng dynasty. It was centered on present-day Yúnnán

in China, with its capital in modern-day Dali City, and the majority of the population were the Bái people (白族 Báizú), now one of the 56 ethnic groups in China).

Nánzhào society was separated into two distinct castes: the administrative White Mywa living in western Yúnnán, and the militaristic Black Mywa in eastern Yúnnán. The rulers of Nánzhào were from the Mengshe tribe of the Black Mywa. Nánzhào modelled its government on the Táng dynasty with ministries (nine instead of six) and imperial examinations. However the system of governance and rule in Nánzhào was essentially feudal. Sons of the Nánzhào aristocracy visited the Táng capital, Chang'an, to receive a Chinese education. At home, the country relied heavily on slaves.

| It was also a militaristic country. An elite vanguard unit called the Luójūzǐ 羅苴子 (which means tiger sons), served as full-time soldiers. For every hundred soldiers, the strongest one was chosen for service in the Luójūzǐ. They were outfitted with red helmets, leather armour, and bronze shields, but went barefoot. Only wounds to the front were allowed and if they suffered any wounds to their back, they were executed. Their commander was called Luó jū zuǒ 羅苴佐 . The king's personal guards, known as the Zhūnǔ qūjū 朱弩佉苴 , were recruited from the Luójūzǐ. |

|  Xì Núluó 細奴邏 (reign 649-674 ) |  Luó Shèng yan 邏盛 (r.674-712) |  Shèng Luópí 盛邏皮 (r.712-728 ) |

Origins of Nánzhào: In 649, the chieftain of the Méngshě 蒙舍 tribe, Xì Núluó 細奴邏 (reign 649-674 ) founded the Great Méng(大蒙) and took the title of Qíjiā wáng (奇嘉王; "Outstanding King"). He acknowledged Táng suzerainty. In 652, Xì Núluó absorbed peacefully the "White Mywa" (白蠻 Báimán) realm of Zhang Lejinqiu, who ruled Ěrhǎi Lake 洱海) and Cāng Mountain 苍山 ; the agreement was consecrated under an iron pillar in Dàlǐ 大理 . Thereafter the White and "Black Mywa" (烏蠻 Wūmán) acted as warriors and ministers respectively. In 655, Xìnúluó sent his eldest son to Cháng'ān 长安 to ask for the Táng dynasty's protection. The Táng emperor appointed Xì Núluó as prefect of Wēizhōu 威州 , sent him an embroidered official robe, and sent troops to defeat rebellious tribes in 672, thus enhancing Xìnúluó 's position. Xì Núluó was succeeded by his son, Luó Shènggyan 邏盛 (r.674-712 ), who travelled to Cháng'ān to make tribute to the Táng . In 704, the Tibetan Empire made the White Mywa tribes into tributaries, whilst subjugating the Black Mywa. In 713, Luó Shènggyan was succeeded by his son, Shèng Luópí 盛邏皮 (r.712-728 ), who was also on good terms with the Táng . He was succeeded by his son, Pí Luógé, in 733. [Note that in this name that follows Yí 彝 naming conventions, the patronymic name is Pí and the given name is Luógé. ] |

Pí Luógé 皮邏閣 (r.about 733-748 ) Pí Luógé 皮邏閣 (r.about 733-748 ) | Pí Luógé 皮邏閣 (r.about 733-748 ) began expanding his realm in the early 730s. He first annexed the neighboring zhào of Méngsui (each tribe was known as a zhào), whose ruler, Zhàoyuan, was blind. Not long after 733, the Táng official Yan Zhenghui cooperated with Pí Luógé in a successful attack on the zhào of Shīlàng 施浪 , and rewarded the Méngshě rulers with titles. Táng-Nánzhào alliance : In the year 737 AD, during the Kāiyuán 開元 reign period (713–741), Pí Luógé united the Six zhàos in succession, establishing a new kingdom called Nánzhào (Southern zhào) ; this did not happen without ferocity: four zhào rulers were caught in a fire during a festival. Pí Luógé had taken a fancy to one of the widows, but she preferred to die of hunger with the people in her besieged city, cursing Pí Luógé, who repented, and went on to extoll her city as the “source of virtue”. In 738, the Táng granted Pí Luógé the Chinese-style name Méng Guīyì 蒙 歸義 ("return to righteousness") and the title of "Prince of Yúnnán". |

Píluógé set up a new capital at Tàihé 太和 in 739, (the site of modern-day Tàihé village, a few miles south of Dàlǐ 大理 ). Located in the heart of the Ěrhǎi valley, the site was ideal: it could be easily defended against attack and it was in the midst of rich farmland. Under the reign of Pí Luógé, the White Mywa were removed from eastern Yúnnán and resettled in the west. The Black and White Mywa were separated to create a more solidified caste system of ministers and warriors. |

Tibet-Nánzhào alliance : When the Chinese prefect of Yúnnán attempted to rob Nánzhào envoys in 750, Gé Luófèng 閣羅鳳 (r.748-779) attacked, killing the prefect and seizing nearby Táng territory. In retaliation, the Táng governor of Jiànnán (see above), Xianyu Zhongtong, attacked Nánzhào with an army of 80,000 soldiers in 75 but he was defeated by Duan Jianwei (段俭魏) with heavy losses (many due to disease) at Xiaguan. In 754, another Táng army of 100,000 soldiers, led by General Li Mi (李宓), approached the kingdom from the north, but never made it past Mu'ege. By the end of 754, Gé Luófèng had established an alliance with the Tibetans against the Táng that would last until 794. In the same year, Nánzhào gained control of the salt marshes of Yanyuan County. Gé Luófèng accepted a Tibetan title and acted as part of the Tibetan Empire. |  Gé Luófèng Gé Luófèng |

Yì Móuxún Yì Móuxún 異牟尋 (r.779-808 ) | Gé Luófèng's son and successor Yì Móuxún 異牟尋 (r.779-808 )continued the pro-Tibetan policy. In 779, Yì Móuxún participated in a large Tibetan attack on the Táng dynasty. However the burden of having to support every single Tibetan military campaign against the Táng soon weighed on him. In 794, he severed ties with Tibet and switched sides to the Táng . Táng-Nánzhào alliance : In 795, Yì Móuxún attacked a Tibetan stronghold in Kūnmíng 昆明 . The Tibetans retaliated in 799 but were repelled by a joint Táng -Nánzhào force. In 801 Nánzhào and Táng in Battle of Dulu , Chinese and Nánzhào's forces defeated a contingent of Tibetan and Abbasid slave soldiers. More than 10,000 Tibetan/Arabs soldiers were killed and some 6,000 captured. Nánzhào captured seven Tibetan cities and five military garrisons while more than a hundred fortifications were destroyed. This defeat shifted the balance of power in favor of the Táng and Nánzhào. |

Expansion of Nánzhào. Expansion of Nánzhào. | Expansion of Nánzhào. During the following reigns, Nánzhào expanded its territory. It conquered the peaceful Pyu city-states (today Myanmar) in the 820s and destroyed the city of Halin in 832, returning in 835 and taking away prisoners into slavery. Nánzhào colonized that area (which became Burma, later, the official English form until 1989 before being renamed Myanmar). |

In 829, King Quàn Fēngyòu 勸豐祐 ( r.823-859) of Nánzhào attacked Yìzhōu 益州 (Chéngdū 成都), but withdrew the following year. The invasion was not to take Sìchuān 四川 but to push the territorial boundaries north and take the resources south of the city. In 830, Nánzhào renewed contact with the Táng empire. The next year, Nánzhào released more than four thousand prisoners of war, including Buddhist monks, Daoist priests, and artisans, who had been captured during the Yìzhōu incident. Frequent visits to Cháng'ān by Nánzhào delegations followed and continued until the end of Emperor Wǔzōng 武宗 ’s reign in 846. During these sixteen years, Nánzhào progressed rapidly in state building. Through its students dispatched to Yìzhōu , Nánzhào borrowed heavily from Táng administrative practice. Quàn Fēngyòu also commissioned Chinese architects from the Táng dynasty to build the Three Pagodas (which remain a famous landmark). Almost simultaneously, in the 830s, Nánzhào conquered the neighboring kingdoms of Kūnlún 昆仑 to the east and Nuwang to the south. |

King Shìlóng 世隆 (r.859-877) started a tug-of-war around the southern Táng circuit of Ānnán 安南; besieging and capturing its capital capital Sòngpíng 宋平 in mid-January 863. Next, Nánzhào laid siege to Junzhou (modern Haiphong). Ten thousand soldiers from Shāndōng and all other armies of the Táng empire were called and concentrated at Halong Bay for reconquering Ānnán. A supply fleet of 1,000 ships from Fújiàn was organized. Táng general Gāo Pián 高駢 , who had made his reputation fighting the Türks and the Tanguts in the north, campaigned from 864 to fall 866 and retook Ānnán. In 869, Shìlóng attacked Chéngdū fiercely for over a month. But Yáng Qìngfù 楊慶復 , military governor of Jiànnán East Circuit (Jiànnán dongchuan), coordinated a rescue operation, recruitinga group of soldiers known as the "Raiders" (突將 Tū jiāng) to aid in the defense of Chéngdū ; Nánzhào suffered a crushing defeat and Shìlóng decided to abort his campaign. Nánzhào invaded again in 874 and reached within 70 km of Chéngdū, seizing Qióngzhōu 邛州 , however they ultimately retreated, being unable to take the capital. In 875, Gāo Pián was appointed by the Táng to lead defenses against Nánzhào, chasing their remaining troops to the Dàdù River (大渡河 Dàdùhé) where he defeated them in a decisive battle. But his plan to continue with an invasion of Nánzhào was rejected. Nánzhào forces were driven from the Bōzhōu 播州 region, modern Guìzhōu 贵州 , in 877 by a local military force organized by the Yang family from Shānxī 山西 . This effectively ended Nánzhào's expansionist campaigns. Shìlóng died in 877. |

Shìlóng's successor, Lóngshùn 隆舜 (r.878-897 ), entered negotiations with the Táng for a marriage alliance in 880, but despite his sincerity, he failed to bring the Princess of Ānhuà (安化長公主 Ānhuà zhǎng gōngzhǔ) to Nánzhào, and was murdered in 897. Further murders made the dynasty come to a bloody end in 902. Finally Duàn Sīpíng 段思平 seized power in 937 and established the Dàlǐ Kingdom (大理国 Dàlǐ Guó Guó ). |

Link back to Table of Contents

10. Hebao silk pouches |

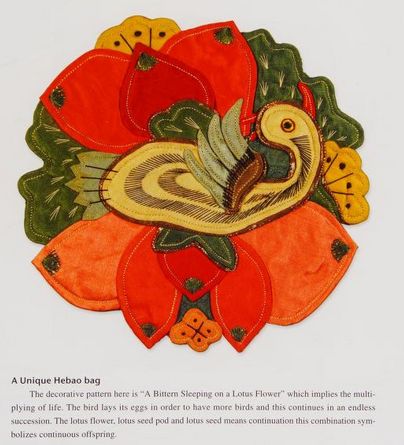

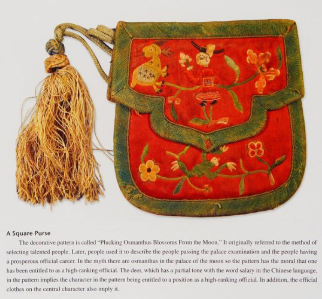

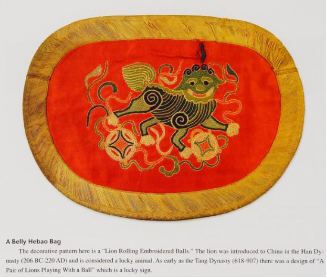

The (interim) “brocade officer” Chief Sāng (桑长史 Sāng zhǎng shǐ) of the Brocade Bureau was astounded that his son was in the game to promote business and the sale of silk embroidered 荷包 hébāo (propitious pouches) in the new 8-11 member Silk Society. Yīngyīng had crafted these from a 缂丝 kèsī (sometimes written “gesi”) tapestry weave, normally using silk on a small scale, often with animal, bird and flower decoration, etc. She had embroidered them with auspicious characters.

|

|

|

|

"Kesi"means "cut silk", as the technique uses short lengths of weft thread that are tucked into the textile. Only the weft threads are visible in the finished fabric. Unlike continuous weft brocade, in kèsī each colour area was woven from a separate bobbin, making the style both technically demanding and time-consuming. This technique first appeared during the Tang dynasty (618–907), and became popular in the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279), reaching its height during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). The style continued to be popular until the early 20th century, and the end of the Qing dynasty in 1911–12.

|  This is a pictophonetic character, with the upper half being the "grass" radical and the lower half representing the pronunciation "hé". This is a pictophonetic character, with the upper half being the "grass" radical and the lower half representing the pronunciation "hé". |

The name of the hébāo comes from the lotus flower " 莲花 Liánhuā" or " 荷 Hé" the lotus leaf, which also refers to lotus flowers.

This also has a meaning of carrying things since Chinese people have long been used to wrap things in lotus (or other) leaves. With the development of needlecraft, their use expanded from "accessory bag" to "purse" and "fragrant bag" in which herbs or perfumes were put to ward off biting insects.

“The hébāo was developed from the nangbao, a type of small bag which would keep one's money, handkerchief and other small items as ancient Chinese clothing did not have any pockets. The most common material for the making of nangbao was leather. The earliest nangbao had to be carried by hand or by back, but with time, the nangbao was improved by people by fastening it to their belts as the earliest nangbao were too inconvenient to carry.

The custom of wearing of pouches dates back to the pre-Qin dynasties period or earlier; the earliest unearthed artefacts of Chinese pouches is one dating from the Spring and Autumn period and the Warring States period.

In the Southern and Northern dynasties, hébāo became one of the most popular form of clothing adornment. They were worn at the waist and were used to carry items (such as seals, keys, handkerchiefs, cigarettes). Incense, pearls, jade, and other valuable items were placed inside the hébāo to dispel evil spirits and foul smells.

In fact, from Eastern Zhou dynasty (770 BC-256 BC) to the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), hébāo were a necessary part of imperial apparel ; they were also widely used by the majority of people. Their make and form showed the status of a person ; they were used as gifts on festive occasions or for marriages, and as a pledge of love.

The hébāo come in different forms : round with a drawstring to close them, shoulder bags with two parts to "ride" over a belt, square or rectangular with a flap that can be fastened with a string to a button, "belly bag" to be tied in front to the belt, or other fancy designs (elliptical, guava, gourd, peach, flower basket, flowers, fish...). They could be made of brocade, and decorated with various designs, also in embossed brocade. Here are some examples :

To view more hébāo and more cloth art, you can set up an account at the Internet Archive, and borrow for an hour the 2007 book by Mo Geng : Chinese Cloth Art, in English translation, from which the three last pictures and the lotus hébāo are copied.

Link back to Table of Contents

11. Money in Tang dynasty |

In the drama, the gamble for money episode 2 mentions “suǒ zi” 索子 and “guàn” 贯

“suǒ zi” 索子 is not a type of money ; it refers to a "thick rope" or to a series of tiles in certain Chinese games such as mahjong, where “suǒ zi” is a "line" in the series of 4 identical "lines" of 9 bamboo design tiles (條子 Tiáozǐ). But mahjong was not yet played in Táng dynasty; other gambling games used the word to refer to a "string" in the game, but a string of coins was a “guàn”.

|  |

Money in Táng dynasty (618 AD - 907 AD) : ever since 五銖 “wǔ zhū coin” (a copper alloy round coin with a square cut out in center, weighing “five zhū” = 3.25 grams) was invented in 汉代 (Trad. 漢代) Hàn dài, Western Hàn dynasty, the weight of coins in China has been roughly around 4 grams. The name of money changed under Jīn to Suí dynasties : “Wén” became the smallest unit of money (increasingly replacing 錢 “qián” simplified now as 钱 ).

1000 wén文 = 1 Guàn 一贯钱 yīguàn qián (i.e. string);

文wén was the chief denomination for “cash” until the introduction of the 元 yuán in the late 19th century. During that dynasty, silver and gold coins appeared and reign titles started to appear on coins.

But monetary economy was not very developed in Táng dynasty: in the beginning, government officials were paid in grain or rices; they only started to be paid in money after 開元 Kāiyuán period (Emperor 玄宗 Xuánzōng's Kāiyuán era 713-741 is usually viewed as one of the golden ages of Chinese history); in late Táng dynasty, monetary payment to government officials disappeared again.

One possible reason is because Táng dynasty took money very seriously and money supply was significantly reduced: starting from Táng dynasty, money was no longer called as qián “cash”; instead it was called as bǎo 寶.

Three types of money were used most extensively in Táng dynasty:

kāiyuán tōng bǎo 開元通寶  | The alloy making the most widely used KYTB was standardized as well as its size (1 inch/2.5 cm diameter) : For the first time we find regulations giving the prescribed coinage alloy: 83% copper, 15% lead, and 2% tin, and private minting was forbidden. |

qián fēng quán bǎo 乾封泉寶 | (one QFQB equals 10 KYTB) ; these were cast under the reign of Emperor 高宗 Gāozōng (649–683) in 666 but one coin weight of 2.4 zhū was the same as a one KYTB coin, and it gave rise to extensive forgery, so the coin was withdrawn after a year. |

qián yuán zhòng bǎo 乾元重寶 | (one QYZB equals 10 or 50 KYTB); issued by Emperor 肅宗 Sùzōng (756–762) to pay the army, the coins of the first issue, in 758, were the equivalent of 10 ordinary cash coins. Each coin weighed 1.6 qián. The second issue, from 759, was of larger coins, one of which was to be the equivalent of 50 cash. |

But copper coins were difficult to carry when large transactions were calculated in terms of strings of coins, therefore, merchants in late Táng times (c. 900 CE) started trading receipts from deposit shops where they had left money or goods. — In addition, around the 6th century, the copper that was needed to make Chinese coins (bronze/copper cash coins) became increasingly scarce.

Therefore, “Fēi qián 飞 钱 /Trad 飛錢 (“flying money”), similar as commercial paper, was invented in Táng dynasty also because the supply of money was limited; money was often forbidden to move across regions; there was a large amount of tax... But it was not yet paper money which appeared in the following dynasty.

Link back to Table of Contents

12. Xiuqiu silk balls |

| In the drama, Yú Shū’s granddaughter played with a silk ball |  |

Xiùqiú 绣球, also known as silk ball or embroidery ball, is a traditional craftwork made by people of the Zhuàng ethnic group in 廣西 Guǎngxī Zhuàng Autonomous Region and passed widely through generations. The silk balls are sewn by young girls and might be shaped like a crescent, a fish, a duck or the usual round, square and octagon.

Xiù means "embroider" or "embroidery" Classifier: 个 Example: 这两个丝球多少钱 Zhè liǎng gè sī qiú duōshǎo qián How much do these two silk balls cost ? | 绣 from left to right is formed tracing:

球 has :

|

The history of xiùqiú dates back 2000 years : they were modeled from an ancient weapon called "fēi tuó" 飞砣 (meaning "flying weight") which was made of two bronze balls connected by a rope and used to swing, flail like, and be thrown in battle or hunt, like in this demo by a man in Zhuàng traditional ethnic costume. |  |

The fabric balls, on the contrary, are not too hard, filled with grain, or, today, rose bark strips and sawdust, and not coming in pairs connected by a rope, but hung with tassels or fringes. They are used in a "pāo xiùqiú" 抛绣球 , a traditional game where two teams compete to throw and catch the ball, sometimes like this : "In competition, the male team and the female team stand on two sides and throw the balls into the small hole (with a diameter of 60 centimeters or less than that) on the top of the 10-meter high wood post " [rules of this "sports" in this LINK] ; there are different variations on this game. In the Táng dynasty, under the short reign of 武则天 Wǔ Zétiān 's son emperor Zhōngzōng 中宗 (705-710), the emperor wanted it to be used to liven up banquets, where xiùqiú were thrown to order drinks, and the silk ball throwing developed into a party game, and even a dance commemorated by poets.

Ordinary people outside the palace appropriated the game and found new variations for it. Over the centuries, Xiùqiú tossing has evolved into a traditional game in festivals marking the blooming season or harvest time. There are various ways of playing this game.

| Surrounded by karst mountains, the ancient city of Jiùzhōu 舊州, Jìngxī 靖西 is built on the confluence of two rivers and is known as the 'living museum of the Zhuang people' ▪️ It is the 'Hometown of Chinese Hydrangeas' and of the silk ball ▪️ Clear rivers flow quietly, waterfalls are spectacular, mountains, especially in the morning mist, make the scenery dreamlike. |  |

| The city has skilled weavers and stitchers who perpetuate a stacked embroidery needlecraft called Duixiù (*) : first, the thread is woven to incorporate vivid colors used to embroider the patterns on the silk balls, achieving a striking relief-3D effect, like on the balls to the left. (Click on GIF to left to view a 6min31 video from August 2024 about the embroidery and the city of Jiùzhōu in Guǎngxī ) |

| To the right, another short video about xiuqiu stitching (click on my Gif excerpt from the full 1min video on YouTube to view it in full) |  |

In a legend, the silk ball was used to save the lover of a beautiful girl who had been falsely accused and tortured. The girl, crying her eyes blind, stitched a ball while pricking her fingers so the blood ran into the threads. She went to see her lover in jail and hung the ball around his neck: in a flash both disappeared and were transported magically to a more peaceful countryside, where they were in good health, married, and had lovely children.

The use of xiùqiú as a token of love thrown by the girl to the boy she fancies was also very traditional; either that or throwing it high over a group of young men who competed for the girl's attention, whoever caught it would be accepted as husband.

| NB. The abstract ‘Dòucǎi ball-flower’ motif in vibrant colors on white porcelain which is popularly known as 'ball flower' pattern in the West, has nothing to do with the xiùqiú : it is inspired by a Japanese motif that emperor Yōngzhèng 雍正 (1723-1735) liked. |  The dòucǎi 斗彩 technique for polychrome designs on porcelain appeared in the reign of the Xuāndé 宣德 Emperor (1426–1435), from which a dish with red and green enamels was excavated at the Jǐngdézhèn 景德镇 kilns. The dòucǎi 斗彩 technique for polychrome designs on porcelain appeared in the reign of the Xuāndé 宣德 Emperor (1426–1435), from which a dish with red and green enamels was excavated at the Jǐngdézhèn 景德镇 kilns. |

Link back to Table of Contents

Recent Discussions

-

direct links to spicy novel stuff7 minutes ago - mparthur

-

What was the last song (non Asian) that you listened to? #211 minutes ago - Anusaya

-

BL Drama Lovers Club13 minutes ago - BabyFeatForever

-

Last Asian Song You Listened To?17 minutes ago - GS

-

Last Korean song you listened?20 minutes ago - puma161

-

Soundtrack Lovers Club25 minutes ago - GS

-

best dramas of 202431 minutes ago - GS

Hottest Discussions

-

***Count to 100,000***14 hours ago

-

The ALPHABET Game [drama /movie version]2 hours ago

-

♡Last letter of a country / town game♡2 hours ago

-

Word Association #42 hours ago

-

10 dramas/movies with ____? #412 minutes ago

ep.1

ep.1

Episode 2

Episode 2

Episode 3

Episode 3

Episode 4

Episode 4

Episode 5

Episode 5

Ep.7

Ep.7

Episode 11

Episode 11

Episode 12

Episode 12

Ep.14

Ep.14

ep.15

ep.15

Ep.16

Ep.16

Ep.18

Ep.18

万贯 [Trad. 萬貫] wàn guàn (= ten thousand strings of cash ; very wealthy, millionaire)

万贯 [Trad. 萬貫] wàn guàn (= ten thousand strings of cash ; very wealthy, millionaire) 索子 suǒ zi (= a thick rope) different from 梭子 suō zi (=shuttle for textile)

索子 suǒ zi (= a thick rope) different from 梭子 suō zi (=shuttle for textile) 文钱 wén qián (culture, thought, + money) , close pronunciation to 揾钱 wèn qián (dialect: to make money)

文钱 wén qián (culture, thought, + money) , close pronunciation to 揾钱 wèn qián (dialect: to make money) 十万 [Trad. 十萬] shí wàn (= hundred thousand)

十万 [Trad. 十萬] shí wàn (= hundred thousand)