Posters of Asian Movies - China

Posters of Asian Movies - China

Haunting. This word feels like it's an overused term. Many art forms are too frequently being described as haunting. But to me, a haunting film is one that stays with the viewer for hours, or even days, after viewing. Its memory refuses to diminish and it demands rumination. A good movie isn't always haunting, and a haunting one isn't always good, but there often is a correlation.

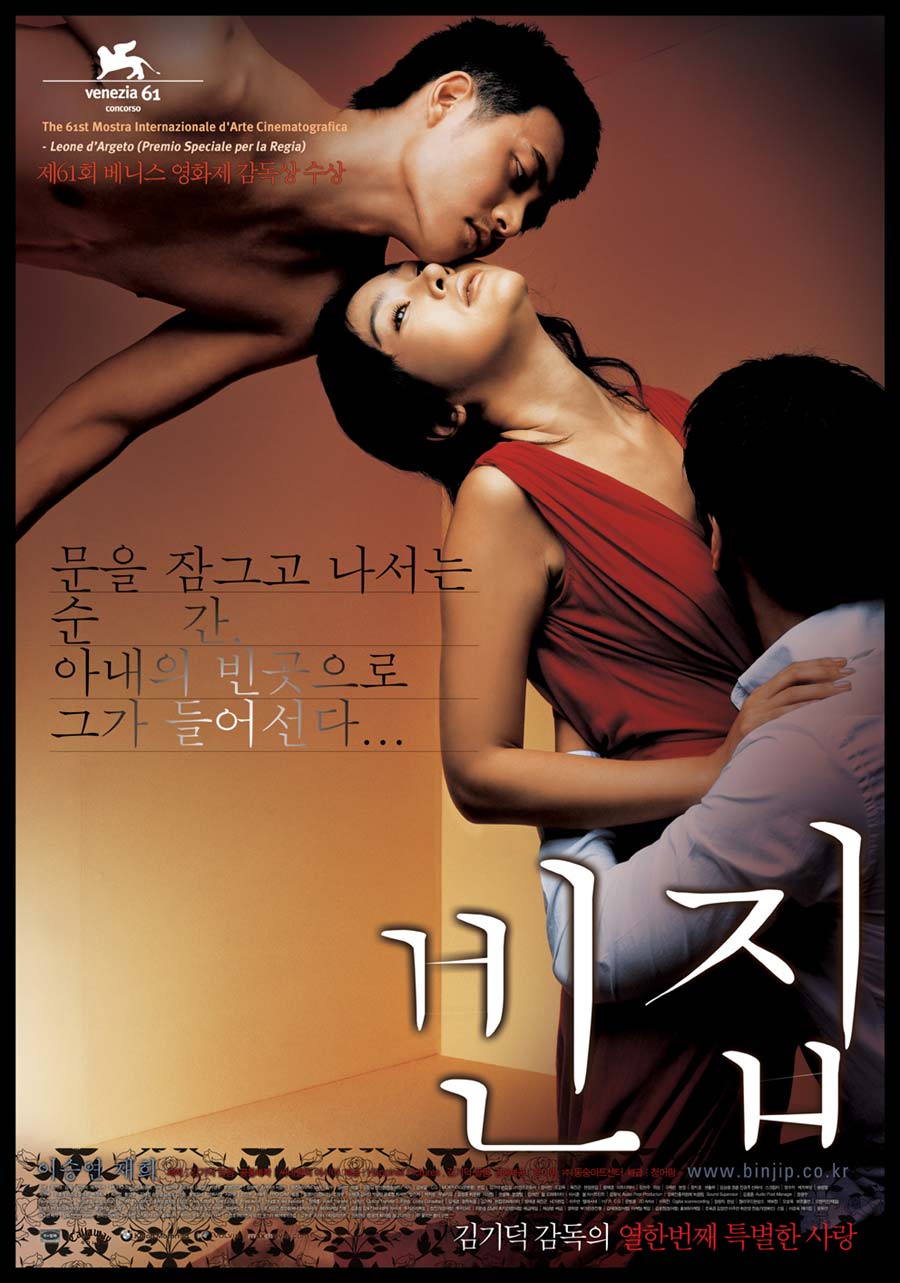

Such is the case with 3-Iron, from acclaimed director Kim Ki-duk (who sadly recently passed away).

This enigmatic and in some ways maddening motion picture has the power to haunt every viewer it reaches. This film is very much in line with the director’s previous films, being a complex exploration of human relationships and communication as well as the violence so often inherent in these aspects of our existence.

One of the most striking aspects of 3-Iron is the way Kim generates tension between the calm, ambient existence of the two protagonists, Tae Suk (Jae Hee) and Sun Hwa (Lee Seung Yeon), and the violent noise of the outside world. This tension is laid bare by the fact that neither of the protagonists utters a word until the final scenes of the film. By eliminating dialogue, Kim forces his characters to interact on a non-verbal level, and it intensifies the manifestations of their emotions.

The whole film is filled with small gestures and a gentle form of communication which is innovative and at times simply delightful. Both actors give outstanding performances, and the range of emotions they convey with mere looks and actions is quite incredible. It's a masterclass of physical acting from both of them.

This silence, combined with the gentle soundtrack and Kim’s dreamy, gorgeous visuals, gives the parts of the film which focus on the strange couple a haunting and beautiful air which is joyful in its innocence, yet sad because the viewers are all too aware that their self-imposed isolation will not endure. Kim constantly reminds viewers of this by shooting the outside world in harsh colors and shadowy darkness, portraying a world filled with selfish, vicious characters.

This silence, combined with the gentle soundtrack and Kim’s dreamy, gorgeous visuals, gives the parts of the film which focus on the strange couple a haunting and beautiful air which is joyful in its innocence, yet sad because the viewers are all too aware that their self-imposed isolation will not endure. Kim constantly reminds viewers of this by shooting the outside world in harsh colors and shadowy darkness, portraying a world filled with selfish, vicious characters.

In the end, Kim offers some form of hope, though typically, this is left very much up to the viewer to interpret and to draw meaning from, as the film’s final act takes a decidedly surrealist turn, with events that may or may not be real, and a climax which is incredibly moving, whilst leaving much to the imagination.

This, for many viewers, will be the main problem with the director’s films, as his decision not to impose any kind of real moral judgment on his characters or to offer any concrete answers to the questions raised can be frustrating. However, for those who enjoy films which stimulate and probe, his works can almost be seen as philosophical tracts which beg for deeper meditation in a way which is hugely rewarding in an age where most films simply spoon feed viewers their plots and secrets.

A masterpiece not to be missed.